|

ShellacReturn to Hand Rubbed Finishes Home Page Under Construction Tung Oil Section

The History and Use of Shellac

Introduction Artisans of the Valley is a museum quality antique restoration and reproduction shop specializing in shellac finishes. Over the years, we have found ourselves explaining shellac finishes and educating our clients as to its use and history, as well as proper maintenance and repair techniques. Shellac has been used for several thousand years, and to experienced finishers and restorers of fine furniture the world over, shellac remains the finish of choice. One of the most elegant finishes for furniture, French Polish, is done with shellac. Conservators and restorers of antiques use shellac for re-finishing antiques. This text is designed to provide a thorough background in this unique product. To the average person, shellac has a jaded history of poor water and heat resistance, difficulties in application, poor drying, and limited durability. We are constantly hit with this persona by clients and especially other woodworkers, always with the classic intolerance of a “white ring under the glass.” Some of these objections are valid, but in general the objects to shellac are unfounded or easily overcome by using proper tools, techniques, and most important - proper product. True Early American antiques were finished in, and must be restored in almost exclusively shellac to maintain their full value. Applying hand cut shellacs is key to matching the original methods and appearance of past craftsmen. This is our primary use of shellac products, but the heritage of this unique compound is far greater than just furniture. Almost everyone has heard of Shellac, but very few truly understand it's origin and common uses. Shellac is perhaps the father of the modern plastics industry; the fact is that the original goal of this industry was to replicate the characteristics of shellac with various additional qualities. These attempts lead to forks and turns in the road to a vast array of industries and products. The original cultivation of shellac was not for the resin as a furniture finish, but rather, for the dye that gives the resin its characteristic color. Shellac is remained an important export commodity for India and Western Europe throughout its history. The use of lac dye can be traced back to 250 AD when it was mentioned by Claudius Aelianus, a Roman writer in a volume on natural history. The first use of shellac as a protective coating appears as early as 1590 in a work by an English writer while visiting India and documenting local cultures, an extract from his text provides one of the earliest known observations of shellac application. "Commenting on a procedure for applying lac to wood still on the lathe he writes "they take a peece of Lac of what colour they will, and as they turne it when it commeth to his fashion they spread the Lac upon the whole peece of woode which presently, with the heat of the turning (melteth the waxe) so that it entreth into the crestes and cleaveth unto it, about the thicknesse of a man's naile: then they burnish it (over) with a broad straw or dry Rushes so (cunningly) that all the woode is covered withall, and it shineth like glasse, most pleasant to behold, and continueth as long as the woode being well looked unto: in this sort they cover all kinde of house-hold stuffe in India". - From Shellac; its production, manufacture, chemistry analysis, commerce and uses. London, Sir I. Pitman & Sons, ltd., 1935 pg. 3. The use of shellac as a furniture finish never caught on in the West until the early 1800’s, it eventually replaced wax, and unrefined oil finishes. It remained the most widely used protective finish for wood until the 1920's and 30's when the nitrocellulose lacquer proliferated the furniture industry. The Life Cycle of a Lac Bug Where does this versatile product come from? It’s nothing more than the organic secretions of a humble scale insect, one of 2000 known species of such creatures known Laccifer Lacca, or the “lac bug.” Lac bugs, about the size of an apple seed, live attached to trees, in great numbers, called lac host trees where they secrete lac resin, the raw material for shellac. These little creatures offer a massive destructive power, but are never the less are a critical part of their environment in many regions. Lac insects lead a short six-month life cycle consisting of four stages: egg, larva, pupa and adult. A six-month cycle offers two harvest seasons per year. Females lay up to 100 eggs in the form of a brood lac, containing the female lac insect attached onto fresh new twigs of trees, known as a lac host trees. The eggs are destined to become larvae as they hatch small and red, roughly 0.5mm, long. Larvas leave the brood lac, or mother cell, and settle on nearby twigs to begin their feast of sap. Well equip for the task ahead of them, each armed a long trunk-like mouthpart, or proboscis, the lac larva draw out tree sap for food. Their first meals begin a process of secretion is exuded from their bodies which is in essence a protective covering to prevent an attack by predators. This secretion eventually forms hard resinous layers, completely covering the bug except for small anal and breathing openings. The insects mature into adults under this protective layer, both sexes become sexually mature in about eight weeks. During this period, the male insect undergoes a complete metamorphosis, or transformation into another form. The male loses his proboscis in exchange for antennae, legs, and a single pair of wings. The male cell is slightly longer than the female cell, and features a small round trap door. When he emerges, using the trap door, his life in the outside world consists of walking over the females, and fertilizing them. He then proceeds to die … The female cell, rounded in shape, and remains fixed to the twig. She retains her mouthparts, but fails to develop any wings or eyes. During development, she forms rudimentary antennae and legs, however she is immobile, existing as shell-like organism with little resemblance to an insect. Females are little more than egg producing organisms. As the female lays her eggs, she continues to grow; all the while increasing lac resin is secretion to maintain a continuously expanding outer layer. After fourteen weeks the female contracts, allowing light into the cell, then lays her eggs. When the eggs hatch they emerge as larvae and the whole process begins all over again. Her ovaries contain a crimson fluid, called lac dye, which resembles cochineal (a coloring used mainly in the food industry and derived from dried bodies of coccus insects). After the cycle has been completed, and around the time when the next generation begin to emerge, the resin encrusted branches are harvested. They are scraped off, dried, and processed to form shellac. A portion of broodlac is retained from the previous crop to produce the new crop. Areas of Cultivation India and Thailand are the main areas in the world where lac is cultivated. Over 90% of Indian lac comes from the States of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Maharashtra, and Orissa. Lac insects thrive on certain trees and the principal lac host trees in India are Palas, Kusum, and Ber. India exports different grades of handmade and machine made shellac, as well as a limited quantity of refuse lac, namely kiri, molamma, etc. Lac production was introduced from India to Thailand where the rain-tree is the principal lac host. Thailand exports sticklac and seedlac. Today India is responsible for 50% of the world production. Most of the finished shellac is exported. Methods of Production After the trees have been infected with broodlac, the crop requires little or no attention until harvest. Cultivation is involves scraping off the twigs, gathering of fresh moisture rich shellac. Fresh harvests are left to dry before being sold. The gathering process usually takes place villages, gathering small quantities brought to local markets, eventually massed for sale to manufacturers or their agents. The quality and value of sticklac depends very much upon a variety of factors such as the host tree, the climate, whether the crop is harvested before or after the emergence of the larvae, and methods of drying and storage. In India, the yield of sticklac averages three quarters the weight of broodlac used. The lac scraped from the branches is known as crude lac or sticklac. Crude lac or stick-lac, consists of the resin, the encrusted insects, lac dye, and twigs. This is crushed, washed, dried to form Seedlac. The Seedlac is then converted into Shellac by hand or machine. Manufacturing Process Wm. Zinsser & Co of New Jersey, USA, is the world's largest shellac firm. About 20 workers bleach and dewax tens of thousands of pounds of shellac each day. The plant is even inspected regularly by rabbis to retain its kosher rating.

Over shellacs the ability to produce cleaner and purer resins developed, however true antique restorers know the tricks of the trade involve the use shellacs to produce a rich, warm, deep patina matching years of oxidation in the woods surface for reproductions or masking the restored finish layers by using hand cut unrefined shellac.

At the end of all the stretching, washing, and refining the shellac is dried. Often in outdoors in the sun. It is then stored in cool dry conditions until ready to be packaged for shipment. Properties of a Natural substance known as Shellac

Shellac is hard, and practically odorless, in the cold, but evolves a characteristic smell on heating or melting. Superior grades are light yellow in color, while the inferior grades range from deep orange brown to almost dark red. It is a powerful bonding material with low thermal conductivity. It is resistant to the action of ultraviolet rays, and has tenacious adhesive qualities, sticking to anything from porous wood to glossy smooth surfaces. If you’ve ever tried to clean it off glass - you’ll understand, and Shellac is one of the only products capable of sealing in the smell of urine! It dries to the touch in less than fifteen minutes, reducing or if properly applied, eliminating drips. It can be softened and molded like clay or dissolved in solvent, melted into existing finishes, and spread whisper thin. A Versatile Compound

Lac By-Products and Derivatives Shellac acid derivatives include Aleuritic Acid, Jalaric acid and Shellolic acid. By-products obtained during manufacture of shellac include molamma, kiri, passewa, shellac wax and lac dye. Molamma is usually in the form of a fine dust, obtained during winnowing, sieving, or washing seedlac; Kiri is the residue retained in the cloth bag after refining seedlac into shellac by hot filtration. It contains sand, insect debris and other impurities; Passewa is obtained by boiling the cloth bag used for refining seedlac and is available as thick slabs; Shellac wax is retrieved from shellac and has properties similar to carnauba wax; Lac dye (laccaic acid) is obtained during the washing of seedlac. Storage The finished product are dry flakes, Dry shellac flakes store indefinitely, under proper conditions, but contrary to what you may hear, it won't store forever in just any location. Sealed bags, preferably vacuum packaged, prevent moister from entering the resins and provide for an almost unlimited shelf life. Dry shellac reacts with itself when exposed to moister, forming polymers that are insoluble in alcohol. Shellacs that have been dewaxed are even more susceptible to this. You can extend the usable life of dry shellac flakes by storing them after purchase in a cool, dry area - a refrigerator is best. A test for suspected old shellac is easy - simply dissolve the flakes in alcohol. Most shellacs should be totally dissolved within three days. If you see a gelatinous un-dissolved mass after this time discard the shellac; it is past its usable life. If you just purchased it, consider returning the batch to your supplier and notify them that this batch is now past its prime. Sometimes in summer months, shellac will cake together. This is known in the industry as "blocking" and is not a sign of bad shellac. Break up the shellac with a hammer and dissolve it in alcohol as usual. Heat causes this, as shellac begins to melt at low temperatures. For use as furniture finish, shellac is dissolved in ethanol, and a chemical process known as etherification begins. Over time, the alcohol chemically modifies the hard shellac resins, ultimately turning them into a sticky gum, which doesn't dry - the result is shellacs reputation for “never drying.” Large manufacturers such as Zinsser have an expiration date, usually three years from the production date, but for the best results and working properties, you achieve better results if you prepare your own shellac from dry flakes. A small stockpile of individual sealed bags is the sign of a good restoration shop. Shellac does solidify properly in hot weather, and this is a problem in many countries. It is best stored in air-conditioned warehouses maintaining a temperature between 14-18 degrees C. Air-conditioned storage ships and containers are often employed to ensure the arrival of shellac reaches its destination in useable condition. Dissolve dry shellac flakes in denatured ethanol, which is sold in most paint stores. It also dissolves in methanol, butyl, and propyl alcohol. Methanol will evaporate the quickest, followed by ethanol, butyl, and propyl alcohol. The last two alcohols, butyl and propyl can be added to shellac dissolved in ethanol in small amounts to act as retardants. Retardants act to slow the evaporation of solvent alcohol and prolong

the functional application time, an important factor when brushing.

Lacquer retardant can also be used, as well as methanol, but these

both impart a very toxic factor so its general use is discouraged. Shellac as a finish is a solution, the solid resins of shellac dissolved in alcohol, usually denatured alcohol. The ratio of dry shellac flakes, in weight, dissolved in liquid volume of alcohol is known as the cut. The traditional stock ratio is 3lbs of flakes per 1 gallon of alcohol. Experience over years of application taught woodworkers that this traditional formula works for almost every basic application. Custom cuts of shellac are often employed to produce specific results. Cuts over 3lb quickly become thick and gel like, and almost unusable as a furniture finish. A light cut, say a 1lb cut, acts as a sealer, a thin unobtrusive layer usually designed to begin the process of grain sealing and raising. A seal coat is often employed as a base for other finishes such as paint, or even a full 3lb cut of shellac. Cuts less than 1lb are employed in a process known as “sizing,” or lightly sealing the grain of a material to reduce the penetration of dies or pigments. Pro’s and Cons All finishes have basic advantages and disadvantages when compared to their colleagues. Shellac directly competes for industry attention with Lacquer, Varnish, Urethane, Acrylic, and Epoxy based finishes.

In the defense of shellac, many of its disadvantages base in misconception and misuse. Two of the most common ones can be easily explained. The first is that it won't dry. This problem can be avoided by using freshly dissolved shellac flakes. The second complaint against shellac is poor moisture resistance. This can be overcome by using dewaxed shellac and fresh pro-duct. Using old shellac solution will decrease its moisture resistance. You can easily prove this. Take a board that has been finished with fresh shellac and after it has fully dried (about a week), pour some water on the finish and let it sit overnight. When you come back the next morning you will still see the puddle of water, but the finish will be only slightly marred. Shellacs ability to withstand water decreases with the age of the film; so don't try this on old finishes. Ironically, shellac is that it resists water vapor very well, in fact defeating its synthetic competition often thought to vastly surpass it under United States Forest Products Laboratory testing. The moisture-excluding effectiveness of wood finishes, or the ability of a finish to prevent moisture vapor from entering the cellular structure of the wood, of shellac exceeded polyurethane, alkyd, and phenolic varnish, and cellulose nitrate based lacquers. Keep in mind that some of the disadvantages, like scratching and marring with alkalis, are easily repaired because of one of shellac's great advantages -- its ease of repair. Shellac Finish Descriptions Descriptions From www.shellac.net Applying Shellac Shellac can be applied by practically any method – brushing, padding, or spraying. Most common applications are a simply brushing on a thin even coat for a finish. Never shake or power mix shellac, it imparts air bubbles and moister in the finish which are very difficult to remove later without completely removing the failed finish. Preparing shellac requires only a slow hand stirring with a flat paint stick. Before brushing saturate the brush with alcohol from tip to ferrel, metal band around brush handle, to activate the brushes ability to smoothly hold and transfer your finish. This also makes the brush easier to clean later. Wipe it clean against the edge of a can before dipping into your shellac. A 1-1/2 lb. cut seems about the best brushing cut, perhaps slightly thinner for a first sizing (sealing) coat. Dip the brush halfway into the shellac each time you need to refresh it, bring the brush out and let the excess shellac run off, then drag it lightly across the top of the jar, or can your using. Starting about 2" in from the edge, drag the brush lightly to the edge, then come back all the way to the other edge. Carefully watch the edges for drips and keep a pad handy to remove them before they begin to dry. Dry drips, flying spits, or runs - otherwise known as goobers, can be removed after the finish dries but are much easier to deal with while its freshly applied. Shellac dries quickly, learn to overlap your coats quickly or distinct lines will form between brush lines. Avoid covering an area with more than brush strokes in each area per coat. There is no issue with air bubbles unless you "slap" the brush against the surface. Overlapping each coat by about a 1/4 inch, work the entire surface from start to finish. Never stop short on any surface, in fact never stop short on a piece. Finish should be applied from start to finish, nonstop. It will take 3-5 coats to reach a deep rich and durable finish. Brush cleaning can be done with alcohol solvents, but standard ammonia cleans shellac brushes because the alkaline ammonia dissolves the acidic shellac. Soap and water finishes the job, and the soap helps soften the bristles.

Cut a piece of cloth roughly 10"-12" square, then fold it up into a pad, a pre-made pad is easier. Pour about 1 ounce of alcohol on the cloth and work the alcohol into the cloth. Then take a squirt bottle of shellac and dispense several thimble-fulls of shellac into the pad. There are two basic methods, a strait along the grain technique that starts a motion before the surface and ends after the pad breaks contact, much like following through with a baseball bat swing or leading with a shotgun at a flying target. On an average size surface, you can return to the start by the time you reach the end and pad on several layers. The second technique is a circular method, pressing lightly and pushing the shellac (almost burnishing) into the pours of the wood. This method takes some practice and you must carefully sense the status of the pad, adding a small amount of shellac continuously to prevent it from sticking. The heat of friction rapidly dries the shellac, and if waxed shellac is used begins to polish the surface. Keep doing this until the surface is tacky and the pad starts to stick. Between wipes, pad the edges. The trick to this is to apply light coats of shellac by keeping the pad moist, not dripping wet. If you can squeeze shellac from the pad, it's too wet. You can prolong the life of a bad between sessions by keeping your pad in a tightly wrapped zip lock back, or a small jar with a tight cap. When the pad begins to fray, discard it - a few cents in cotton will waste hours of work if you impart fibers into your finish. The first application of shellac, brush, spray, or pad, should penetrate quickly and be dry enough to scuff-sand with 320 sandpaper, this removes the raised fibers in about an hour. After the first coat, rub using to maroon synthetic fiber pads or 000 regular steel wool between applications. After three coats, let the finish dry for twelve to twenty-four hours, depending on humidity. It takes three to five coats to reach a full polished finish. Then rub the finish out with 0000 steel wool, using wax thinned with mineral spirits as a lubricant. Products like Briwax are perfect for this process. After the wax dries to a haze, wipe the excess wax off with a soft cotton cloth, and then polish with a nylon stocking. This leaves a very mellow, hand-rubbed satin finish. Repairs to Shellac Finishes: Shellac surface repairs are simple, apply a thin coat of alcohol on a pad, and then lightly work as if applying a coat. For more substantial finish damage use a 1lb cut instead of just alcohol. You can fill deep scratches using a heavy cut (4lb or more) applied with an artist's brush like a #1 or #2. If the scratch has gone through the finish and the stain, you can mix the shellac with alcohol soluble dyes or pigments to match to original color. White water spots can be treated the same way, but usually only with straight alcohol.

Conclusion: Although many have conceded or celebrated demise of shellac's dominance as a furniture finish, antique collectors and restorers find this a sin, these artificial finishes may be perceived as waterproof and more durable, but they hide the natural beauty of wood under a cataract of plastic film. Despite the attempts by scientists to duplicate shellac synthetically, and the thousands of useful products resulting from their efforts, a little Indian bug still secretes the best and most astonishing furniture finish.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

home | company

background | woodcarving & sculpture

| period furniture custom built-in's | services | commissioning process museum/historical affiliations | educational services | craftsmen links sitemap | search |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Artisans of the Valley Hand Crafted Custom Woodworking Stanley D. Saperstein Eric M. Saperstein Our studio and showrooms are open by appointment. Please call ahead so we don't miss you! (609) 637-0450 Fax (609) 637-0452 e-mail: woodworkers@artisansofthevalley.com |

The sticklac is crushed and sieved to remove sand and dust. It

is then washed, breaking up the encrusted twigs and insect bodies,

plus allowing the lac dye to wash out. The decaying insect bodies

offer a deep red water that can be reduced into a concentrated

dye. The remaining resin is dried, winnowed, meaning fanned and

separated, then sieved to get the commercial variety of seedlac.

The dusty lac eliminated by sieving is known as molamma lac or

refuse lac.

The sticklac is crushed and sieved to remove sand and dust. It

is then washed, breaking up the encrusted twigs and insect bodies,

plus allowing the lac dye to wash out. The decaying insect bodies

offer a deep red water that can be reduced into a concentrated

dye. The remaining resin is dried, winnowed, meaning fanned and

separated, then sieved to get the commercial variety of seedlac.

The dusty lac eliminated by sieving is known as molamma lac or

refuse lac. The lac dye was removed by the initial washing of the shellac resin

in large kettles, which is also the first step in preparing the

resin. Traditionally seedlac is processed by hand in long narrow

cloth bags, heated by a charcoal fire. The cleaned shellac is slowly

forced out leaving impurities such as insect bodies or twigs inside

the bag.

The lac dye was removed by the initial washing of the shellac resin

in large kettles, which is also the first step in preparing the

resin. Traditionally seedlac is processed by hand in long narrow

cloth bags, heated by a charcoal fire. The cleaned shellac is slowly

forced out leaving impurities such as insect bodies or twigs inside

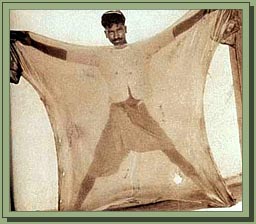

the bag.  The residue left inside the cloth bag is another variety of refuse

lac known as Kirilac. The filtered mass is drawn into sheets approximately

0.5cm thick and thinner by skilled workmen and made into different

varieties that constitute commercial shellac e.g. Lemon I Shellac,

Lemon II Shellac, Buttonlac and Standard I Shellac. Shellac varies

in color from yellow to deep orange. When bleached it is called

white shellac.

The residue left inside the cloth bag is another variety of refuse

lac known as Kirilac. The filtered mass is drawn into sheets approximately

0.5cm thick and thinner by skilled workmen and made into different

varieties that constitute commercial shellac e.g. Lemon I Shellac,

Lemon II Shellac, Buttonlac and Standard I Shellac. Shellac varies

in color from yellow to deep orange. When bleached it is called

white shellac. Machine

made Shellac is produced by either melting using steam heat and

squeezing the soft molten lac through filter; by means

of hydraulic presses; or using solvents. Machines, rather than

the traditional hand processing are being increasingly used by

the lac Industry.

Machine

made Shellac is produced by either melting using steam heat and

squeezing the soft molten lac through filter; by means

of hydraulic presses; or using solvents. Machines, rather than

the traditional hand processing are being increasingly used by

the lac Industry.

Synthetic resins have for the most part displaced Shellac’s

leading role in many products, but the public's incessant return

to ‘natural' and non-toxic compounds may be leading to an

encouraging comeback. As obvious from it’s use as food preservative

and coloring, shellac is entirely non-toxic and FDA approved.

Synthetic resins have for the most part displaced Shellac’s

leading role in many products, but the public's incessant return

to ‘natural' and non-toxic compounds may be leading to an

encouraging comeback. As obvious from it’s use as food preservative

and coloring, shellac is entirely non-toxic and FDA approved. The

Zinsser Company is currently the largest US shellac importer/supplier.

Their name is obviously associated with "Bulls Eye" brand shellac,

but Zinsser reports the top four uses for shellac are actually

pharmaceutical, confectionery, hats, and food coatings, in order

from highest to

lowest. Protective

coatings for wood ranks about number eight.

The

Zinsser Company is currently the largest US shellac importer/supplier.

Their name is obviously associated with "Bulls Eye" brand shellac,

but Zinsser reports the top four uses for shellac are actually

pharmaceutical, confectionery, hats, and food coatings, in order

from highest to

lowest. Protective

coatings for wood ranks about number eight.

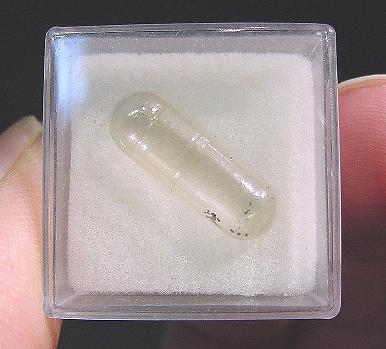

Pharmaceutical - Shellac is used to coat enteric

pills so that they do not dissolve in the stomach, but in the lower

intestine,

which alleviates upset stomachs.

Pharmaceutical - Shellac is used to coat enteric

pills so that they do not dissolve in the stomach, but in the lower

intestine,

which alleviates upset stomachs.

Shellac is a common additive to lipstick and makeup products. Added to the finish and improving the binding ability of these products.

Shellac is a common additive to lipstick and makeup products. Added to the finish and improving the binding ability of these products.

Natural finish prefers natural brushes; Fitch

brushes are usually pure skunk hair, but some have soft badger

hair on the outside

to produce a smooth finish and a center of skunk hair to give

the brush body. A brush is worth it’s weight in gold as they

say, you'll quickly realize the value of a good natural brush

in just a few minutes of use. Pure white china bristle scores a

second

tier, and is best if your use will be sporadic and a more disposable

price tag is required. Never use a synthetic brush, or absolutely

never a foam brush.

Natural finish prefers natural brushes; Fitch

brushes are usually pure skunk hair, but some have soft badger

hair on the outside

to produce a smooth finish and a center of skunk hair to give

the brush body. A brush is worth it’s weight in gold as they

say, you'll quickly realize the value of a good natural brush

in just a few minutes of use. Pure white china bristle scores a

second

tier, and is best if your use will be sporadic and a more disposable

price tag is required. Never use a synthetic brush, or absolutely

never a foam brush.  A less known and practiced technique is called padding, a process

that takes advantage of shellac's rapid drying capabilities and

produces a fine thin layer without brush marks or drips. Padding

works best on flat surfaces, but can be useful on carving or rounded

areas once you gain some experience. Use a 2 lb. cut shellac and

some padding cloth or a finishing pad, often marketed as a French

polishing cloth. It should be as lint-free as possible. Do not

use cotton T-shirt type cloth or cheesecloth, and most definitely

never use a paper towel!

A less known and practiced technique is called padding, a process

that takes advantage of shellac's rapid drying capabilities and

produces a fine thin layer without brush marks or drips. Padding

works best on flat surfaces, but can be useful on carving or rounded

areas once you gain some experience. Use a 2 lb. cut shellac and

some padding cloth or a finishing pad, often marketed as a French

polishing cloth. It should be as lint-free as possible. Do not

use cotton T-shirt type cloth or cheesecloth, and most definitely

never use a paper towel!

To test for a shellac finish, dab some alcohol

on an inconspicuous area such as behind a leg. If the finish gets

tacky, it's shellac.

Artisans specializes in shellac finish restoration and reproduction,

and can provide all related services.

To test for a shellac finish, dab some alcohol

on an inconspicuous area such as behind a leg. If the finish gets

tacky, it's shellac.

Artisans specializes in shellac finish restoration and reproduction,

and can provide all related services.